Gradually, then suddenly!

What Ernest Hemingway can teach us about living with legacy core systems.

“How did you go bankrupt?

“Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

Incumbent banks running legacy core systems have something in common with Mike Campbell, the Scottish war veteran who describes the experience of going bankrupt in Hemingway’s novel.

At first, banks feel the constraints of legacy gradually. Getting things done takes too much time. The cost of managing old systems rises, forcing down investment in innovation. As a result, the cost-to-income ratio, the metric that every bank CEO lives by, deteriorates.

Mathieu Charles, Vice President of Customer Strategy at Temenos, understands this process well. He oversees the Temenos Value Benchmark (TVB)1, the in-house research program that aggregates data from over 150 banks worldwide to demonstrate the value of technology investment.

“The cost of legacy,” says Charles, is that you can’t really be customer-centric, and you can’t innovate at the pace you want. You start to fall behind, either slowly or quickly.

Banks experiencing legacy constraints typically have “a bit of legacy here and there, but a bit of modern software as well,” says Charles. “This kind of bank might have COBOL running in its core, but it has probably invested in APIs and microservices as well. A couple of KPIs sit in the red; a couple are green. All in all, the bank works. But it’s not as efficient as it could be.”

A bank primed for sudden legacy-related crisis looks different. Charles cites the case of one institution in this category: “They were spending 18% of revenues on IT, which is around twice the global average for banks in our survey,” he says. “Their costs accounted for 90% of income, which is 50% higher than average. And their spend on growth and innovation was zero.

“At this point, your infrastructure, your IT, really doesn’t work. You’re running the risk of outages or a botched upgrade. All of the KPIs are in the red, and you must modernize them. You have to do something.”

Over the past decade, regulators have become increasingly interested in the tipping point between gradual and sudden decline. The European Central Bank, for example, actively investigates how digitalization affects banks’ risk profiles. Understanding how digitalization creates a need for “optimizing legacy systems” is one of the “sound practices” it recommends.

In the wake of a sudden crisis, the focus can become more direct. In 2021, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority published a major audit of legacy systems across the financial services sector. The study found that 58% of UK financial institutions relied upon “some” legacy applications. A further 33% confessed that “most” of their applications could be described as legacy.

In testimony to an earlier UK parliamentary inquiry, Charles Randall, the then chair of the Financial Conduct Authority, was unusually direct in describing the attitude to legacy systems regulators wanted to discourage. “Some [banks]. . . need to upgrade and update systems that, frankly, have been underinvested for a long time. They have a big legacy system problem, and they need to migrate to a new generation of systems that will provide the services that consumers need. We need to have a level of intervention that ensures the management. . . does not sit there saying: ‘This is such a nightmare; I will leave it to the next lot.’”

Time-to-market: the leading metric of legacy decline

When Mathieu Charles and his team at TVB meet new clients, they ask multiple questions about legacy technology — some quantitative, others qualitative. The list of legacy indicators includes volumes of data duplication, the level of automated workflows, the percentage of transactions that occur via straight-through processing and the extent of automated exception handling.

But the primary indicators focus on the health of the business. “Probably the most important metric is Time-to-Market (TTM),” Charles says. “If you have a good product factory that’s really integrated with your core, and you have graphical configuration capability, you will get to market quicker than the competition. You will be shipping your product and making money while your competitors are still coding and testing new applications to make sure they integrate with their legacy core systems.”

The difference can be substantial. “In retail banking,” says Charles, “the average TTM for new products is about 30 weeks. Best-in-class performance is much faster: around eight to ten weeks.”

Much depends on the kind of legacy code at issue. “We all talk about legacy,” says Charles. “But what is it? Is it C++ from five years ago? We can all agree that COBOL is legacy. But you have some banks with a bit of legacy where the business model works well. For example, I have seen banks with a legacy core running on mainframes and including a bit of COBOL that have better TTM for existing products than some banks using modern core banking systems.

“Their TTM remains competitive because they have a simple set of products and it’s easy to configure simple changes. However, a bank like this will struggle in other areas, including exhaustive product catalogues and depth of features. They simply can’t code in the morning and deploy in the afternoon.”

The legacy signals in your organization’s IT spend

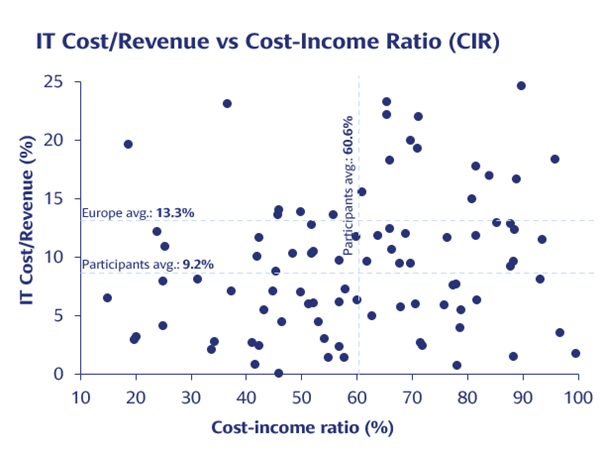

Other key metrics include IT expenditure as a percentage of revenue. TVB’s data records that European banks spend 13.3% revenues on IT, compared to a global average of 9.2%. Charles attributes these higher levels to a mix of factors. For some banks on the continent, above-average spend signals investment in innovation and IT talent. For others, IT costs rise above the norm because of the need to manage legacy systems.

Because IT spend alone is potentially an ambiguous indicator, TVB usually examines this metric alongside others. For example, the combination of above-average IT expenditure and a high cost-to-income ratio signals that legacy technology is probably acting as a constraint.

TVB has plotted these two metrics for participating banks in the scatter chart on this page. The banks in the upper right-hand quadrant with high IT expenditure and high cost-to-income ratios run the biggest legacy-related risks. Perhaps the key takeaway here is the diversity of the landscape: it’s clear that Europe’s banks vary substantially in their approach to legacy and modernization.

[Source: Temenos Value Benchmark]

The drivers of modernization: cost, obsolescence, regulation, innovation

The way in which European banks run their core systems is changing radically. Before the Great Financial Crisis, large in-house teams running on-premises systems were the norm. In the wake of the crisis, a wave of modernization began. Today, it’s often the banks that didn’t participate in that wave that find themselves struggling.

“The banks that get to the point of saying they have to change their core are invariably driven to that decision by the cost of running and maintaining these systems,” says Cormac Flanagan, Head of Product Management, Temenos. “Or it’s obsolescence. They know there are bits of [their core systems] that are going to go End of Support. In the case of larger banks, they can be worried their ageing COBOL programmers are going to retire.”

The increasing need to change legacy systems to cope with new regulations or launch new products is another driver, says Flanagan. “The cadence of change that they need to bring to bear on their core system has increased. They need to do it more often. So they are looking for solutions that enable much more flexibility and ease of change.”

Two perspectives typically collide when the prospect of modernizing core systems is discussed within incumbent banks. The first, typically associated with professionals on the “run” side of the business, is based on avoiding the cost and risk of disrupting systems that may not be perfect but remain largely performant and resilient.

The second opposing perspective is sometimes associated with executives responsible for developing new products and fostering deeper customer relationships. These executives worry about how the cost of managing legacy systems squeezes the funds available for innovation. From experience, they know how legacy core systems can extend TTM.

Where modernization emerges as the chosen solution, the changes are typically progressive or gradual, especially among Tier One and Tier Two banks running multiple cores. As Flanagan puts it: “Potentially, they’ll stand up a new front-to-back system, perhaps for a new greenfield brand in one line of business, get new clients on that, prove its resilience, prove it works at scale. And then they’ll turn around to the rest of the bank, internally, and say to all the legacy guys who would [worry about] resilience, performance: ‘No, it does work, it does scale, we’re moving you now.’”

What is the cost of doing nothing?

For a man who spends his life benchmarking bank performance, Mathieu Charles is keenly aware that any discussion about core systems needs to go beyond KPIs.

“In any bank with some degree of legacy, modernization is not about installing a piece of software that’s going to make your KPIs move from here to there,” says Charles.

It’s a much more subtle conversation. What is your bank’s business model? How do you want to compete in the future? Where do you want to be in five or ten years? Given the pace of change and innovation and the demands of the customer base, what do you need to do to remain competitive? And what is the cost of doing nothing?”

Ultimately, of course, the cost of doing nothing is high. It accumulates on several fronts, including poor TTM, technical debt, skills scarcity and compliance costs. Then there are the larger opportunity costs: the difficulties of fully exploiting cloud-native technology, rolling out data-enabled operations or exploring the potential of Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS), Banking-as-a-Platform (BaaP) or Open Banking.

These costs have never loomed larger. Equally, the risk of Big Bang modernization projects is giving way to progressive approaches enabled by SaaS and composable software design. As banks emerge from the legacy trap – gradually, then suddenly – the dynamic becomes positive rather than negative. As the software guru Tim O’Reilly argues in the context of technology adoption: “Small changes accumulate, and suddenly the world is a different place.”

Learn more about Temenos Core Banking here.

About Temenos Value Benchmark

The Temenos Value Benchmark (TVB) is a strategic survey-based program designed to measure the business and IT metrics and best practices enabled by investment in technology. TVB is a mature research program: 150 banks worldwide currently participate, contributing responses to quantitative and qualitative questions that allow us to develop performance benchmarks across eight business- and IT-related domains. Members receive a customized report free of charge, comparing their performance with their peers. TVB anonymizes peer group data, ensuring that no individual bank’s data is ever disclosed to any of the survey’s other participants. To learn more, visit TVB’s homepage.